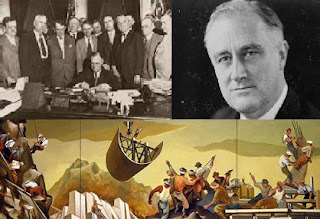

The United States was in the midst of the Great

Depression from 1929-1941. As part of

FDR’s administration, the New Deal was proposed in 1932. Part of the New Deal was the creation of the

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) which was a federally funded organization

that put thousands of Americans to work.

The work that the CCC would complete reflected FDR’s deep commitment to

conservation. In his plea for the New

Deal’s passage, he declared “the forests are the lungs of our land [which]

purify our air and give fresh strength to our people.” At the time, the national forests of our

country were in deplorable condition as a result of over harvesting, forest

fires, and little replanting which increased the problem of erosion.

The CCC became known as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army.” Unemployed, unmarried U.S. male citizens

between the ages of 18-26 were hired as part of the CCC. These young men had to be healthy able-bodied

workers as they would be required to perform hard physical labor. These young men had to enlist for a minimum

of 6 months and were allowed to re-enlist.

They were paid $30 a month and were supplemented with basic as well as

vocational education.

Under the guidance of the Departments of Interior and Agriculture, the CCC fought forest fires, planted trees, cleared and maintained access roads, re-seeded grazing lands, and implemented soil-erosion controls.

|

| The CCC Planting Trees |

They built wildlife refuges, fish-rearing facilities, water storage basins, and animal shelters. FDR even authorized the construction of bridges and campground facilities in order for Americans to be able to enjoy the beauty of America’s natural landscape and resources.

Now with the workforce of the CCC, the National Forest

Service would commence what would become known as the Penny Pines program. For a penny a pine tree seedling, the CCC

would begin replanting and growing pines in National nurseries throughout the

country. Pines could be purchased by

organizations and individuals. The

spirit of this program became a patriotic duty and buckets for pennies were set

up at local post offices and stores.

Unfortunately, not only did the Great Depression bring a monetary

drought, but there were states which could not participate due to prolonged rain

droughts. In these cases, the National

Forest Service recommended that the pines be planted on private lands.

In 1939, then President General Mrs. Henry M. Robert

chose the Penny Pine program as one of her Golden Jubilee National

Projects. The program commenced in 1939

and was to culminate in 1941 on the NSDAR 50th anniversary. The goal of the Penny Pine program was to

have each chapter pledge not less than one acre of pine seedlings which was the

equivalent of 500 trees per chapter at a cost of $5.

At the end of the project, many state societies had planted

a forest. The SCDAR refers to its forest

as the State Tribute Grove. The SCDAR

State Tribute Grove contains ¾ acre or 375 trees. In the SCDAR 1946 yearbook, there is a

reference to our State Tribute Grove.

From the yearbook of 1946, the information reads as follows:

On motion of

Mrs. Wise and seconded by Mrs. von Tresckow, it was voted to buy for the

"Penny Pine Project" a bronze plaque for $30 F.O.B. Cincinnati with

the correction of placing the DAR Insignia at the top instead of at the

bottom as pictured in the blue print. The inscription reads, "These

Trees Dedicated in Honor of the Living, and in Memory of the Dead From South

Carolina in the Second World War." Erected by SCDAR in

1946. This plaque will be placed on a boulder where seedlings have

been planted along highway No. 1 approximately 4 miles east of McBee.

These pines are at a suitable size to be dedicated. The State

Foresty Department offers to assist and place the plaque on the shoulder.

Dedication will be in September and all shall be notified.

The actual date of the dedication was October 11, 1946. Governor Strom Thurmond was the speaker for the dedication. Mrs. Henry Munnerlyn was the State Regent.

If you are wondering why there was a lapse in time between the culmination of the project and the placement of the monument at the State Tribute Grove, this was mainly due to the entrance of the United States in World War II. Priorities and needs changed to meet the demands from the necessities of war. In addition, the ability to assemble in large groups was halted to protect our citizens from the possibility of attack such as was done at Pearl Harbor. There were no state conferences held, and our state officers took on an extra year of their term of office since an election could not be held.

If you are wondering why there was a lapse in time between the culmination of the project and the placement of the monument at the State Tribute Grove, this was mainly due to the entrance of the United States in World War II. Priorities and needs changed to meet the demands from the necessities of war. In addition, the ability to assemble in large groups was halted to protect our citizens from the possibility of attack such as was done at Pearl Harbor. There were no state conferences held, and our state officers took on an extra year of their term of office since an election could not be held.

Let’s look more in depth at the who, what, when, where,

and why concerning the SCDAR State Tribute Grove and its current use as a preserve

for the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker.

In the 1930s

here in South Carolina, farmers in the rural area where the SCDAR forest is

located were struggling to survive with infertile, sandy soil. The U.S. Department of Agriculture developed

the Submarginal Lands Programs and agreed to purchase lands and resettle those farmers

that met qualifications. The project was

known as the Sandhills Lands project.

It was all Federal land, and 45,000 acres became the National Wildlife Refuge. The South Carolina Forestry Commission was leased 45,000 acres from 1939-1990 for multiple use forestry benefits, i.e. a working forest. While some of the acreage of land was farmland, a vast majority of the acreage of lands was timbered, some “cut over” and not replanted. The South Carolina Forestry Commission began replanting the forest to reestablish the forest that had once covered the entire area. The Commission also sustainably harvested the forest which created a perpetual forest through rotational plantings, thinning, and removal. This working forest of which our tribute grove is located supported forest operations here and for all SCFC properties throughout the state.

|

| An example of submarginal lands that became part of the Resettlement Act and Sandhills Lands Project. |

It was all Federal land, and 45,000 acres became the National Wildlife Refuge. The South Carolina Forestry Commission was leased 45,000 acres from 1939-1990 for multiple use forestry benefits, i.e. a working forest. While some of the acreage of land was farmland, a vast majority of the acreage of lands was timbered, some “cut over” and not replanted. The South Carolina Forestry Commission began replanting the forest to reestablish the forest that had once covered the entire area. The Commission also sustainably harvested the forest which created a perpetual forest through rotational plantings, thinning, and removal. This working forest of which our tribute grove is located supported forest operations here and for all SCFC properties throughout the state.

In 1990 the lease ended, the SC

Forestry Commission then began managing the forest for US Fish and Wildlife

through an exchange program. Through the exchange program, management of the

property includes fire protection, control burning, and reforestation for 25

years.

That same year, the forest, of which our grove is a part was also designated as a preserve for the red-cockaded woodpecker. The red-cockaded woodpecker was the first species to be listed as endangered in 1970 and to receive federal protection under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. The property's sole purpose is to support the recovery of this endangered species.

|

| A submarginal land is planted with trees to begin the revitalization of the area. |

That same year, the forest, of which our grove is a part was also designated as a preserve for the red-cockaded woodpecker. The red-cockaded woodpecker was the first species to be listed as endangered in 1970 and to receive federal protection under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. The property's sole purpose is to support the recovery of this endangered species.

|

| President Nixon signs the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Strom Thurmond is on the right side of the picture. |

History of the Red-cockaded Woodpecker

The red-cockaded woodpecker is a small woodpecker that is

about the size of a common cardinal or robin and has a lifespan that averages

sixteen years. It is approximately seven

inches long with a wingspan of about fifteen inches. It eats mostly insects, fruits, and

nuts. Its back is barred with black and

white horizontal stripes. Its most

distinguishing feature is a black cap and nape that encircles large white cheek

patches. The male has small red streak

on each side of its black cap which gives it its name. It is rarely visible except during breeding

season and when defending its territory.

These woodpeckers are unique

in two ways. (1) It is the only

woodpecker that excavates its nesting and roosting cavities in living trees:

preferably old-growth longleaf or loblolly pines, and (2) the red-cockaded

woodpecker lives within a tight-knit extended family community of breeding

birds and helper birds.

The red-cockaded

woodpecker feeds primarily on wood-boring insects like beetles, wood roaches,

ants, centipedes, caterpillars, and spiders. Occasionally the adults will be

observed feeding on blueberry, sweet bay berries, and even poison ivy.

The red-cockaded woodpecker

once thrived in the vast stands of pines that stretched from the Atlantic coast

to eastern Oklahoma. Unfortunately, the

farming practices of European settlers in which land was cleared as well as the

changes in timber management combined to drive the territorial and

non-migratory bird to extinction. The

red-cockaded woodpecker, often referred to simply as the "RCW," was

placed on the endangered species list in 1970. While recovery efforts continue,

the population is currently estimated by USFWS to be roughly 17,500 birds

living in about 8,000 family groups, up from an estimated 12,500 birds and

5,000 groups a decade ago. In South

Carolina, the RCW is listed as imperiled.

RCWs

are monitored based on the number of groups (a breeding pair with 0 to 7

helpers) and the clusters on which they depend (the actual physical cavity

trees and acreage surrounding those trees). In 2000, there were an estimated

14,068 red-cockaded woodpeckers living in 5,627 known active clusters across

eleven states; this number represents only 3 percent of the estimated RCW

abundance at the time of European settlement.

RCW populations on public lands in South Carolina are designated by recovery unit. Our state has 3 recovery units. Within the Sandhills unit, there are 7 designated population areas. Each population has a designated role in recovery. Sandhills State Forest is a Secondary recovery location that will have at least 250 units at recovery. Currently, the forest has 57 groups with a goal of having 127 groups.

RCW populations on public lands in South Carolina are designated by recovery unit. Our state has 3 recovery units. Within the Sandhills unit, there are 7 designated population areas. Each population has a designated role in recovery. Sandhills State Forest is a Secondary recovery location that will have at least 250 units at recovery. Currently, the forest has 57 groups with a goal of having 127 groups.

In order to survive and prosper,

the RCW requires open, park-like forested landscapes of longleaf pine.

Home ranges can be from 70-500 acres depending on habitat quality, namely the

presence of open pine stands that have been frequently burned. RCWs

have evolved in a fire-dominated ecosystem. The history of fire in the

southeast has come about through frequent lightning strikes as well as using

fire to clear land and improve hunting grounds. Those fires

resulted in an open forest with large pines, very little midstory and diverse

herbaceous ground cover. The conditions are the ideal habitat for RCWs

and other species of the longleaf pine ecosystem. Mature longleaf pine

trees are also a necessity because the older trees often fall prey to a fungus

called red-heart disease. This fungus softens the core of the tree,

making it easier for the woodpecker to create its nesting and roosting

cavities.

The

cavity trees must be in open stands with little or no hardwood midstory and

little or no hardwood in the canopy. Once the midstory reaches cavity height,

RCWs typically abandon the cluster. Due

to fire suppression, allowing for the presence of a dense midstory, much of the

currently available habitat has become unsuitable for RCW.

In South Carolina, there are two primary threats that affect the availability of habitat, and, ultimately, RCW recovery now and in the future. The first is a lack of prescribed fire in existing and potential habitats. It has become increasingly difficult for private landowners and government agencies to burn their properties for wildlife management because of liability issues. Until this problem is solved, the ultimate result will be less suitable habitat for RCWs and other wildlife.

The second major threat to RCWs in South Carolina is the

risk of natural catastrophes, specifically hurricanes. The coastal plain is the home of nearly all

RCWs in South Carolina. Hurricane force

winds make the trees with cavities susceptible to being blown down or having

the portion of the tree at that soft spot and above ripped off. As a result, the foraging habitat can be

devastated.

To aid the efforts to preserve the habitat for the RCW

and increase its number, South Carolina became the second state to enroll in the

Safe Harbor Program. The ultimate

efforts of this program are designed tomeet recovery criteria of the RCW in

South Carolina thus facilitating the removal of the species from the endangered

species list.

Carolina

Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge History

Carolina Sandhills National

Wildlife Refuge was created in 1939. Its establishing purpose was to provide

habitat for migratory birds, to demonstrate sound management practices that

enhance natural resource conservation, and to provide wildlife-oriented

recreation opportunities.

The land was badly eroded and very little wildlife was to be found when the refuge was purchased by the federal government under the provisions of the Resettlement Act. Efforts began immediately to restore this damaged, barren land to a healthy, rich habitat for the plants and animals that once lived here.

The land was badly eroded and very little wildlife was to be found when the refuge was purchased by the federal government under the provisions of the Resettlement Act. Efforts began immediately to restore this damaged, barren land to a healthy, rich habitat for the plants and animals that once lived here.

Over time, the

responsibilities have been added for restoration and enhancement of longleaf

pine habitat for the benefit of the RCW. The refuge

operates under mandates to provide environmental education and interpretation

of its work. Habitat improvement and restoration of native plant communities,

monitoring the populations of the RCW and other species, and assessing the

impacts of management actions on the wildlife and habitats are critical

elements in the refuge's operations.

Today, Carolina Sandhills

National Wildlife Refuge is comprised of 47,850 acres, including fee ownership

of 45,348 acres, and nine conservation easements totaling 2,502 acres. The

majority of the refuge lies in Chesterfield County, South Carolina. There is

one fee title tract totaling 210 acres in Marlboro County. Numerous small

creeks and tributaries, along with thirty man-made lakes and ponds and 1,200

acres of fields, support a diversity of habitats for wildlife.

One final note

Some of the

state societies own and have control over the forest they planted as part of the 50th Jubilee project. The SCDAR does not own its grove but is proud to know that its use

preserves and protects an endangered species from becoming extinct.